Liam Young in conversation with Claudia Pasquero and Marco Poletto.

Marco Poletto (MP):

You have made travelling to remote locations one of your main tools for architectural research. What insights are you getting from engaging with such peculiar sites?

Liam Young (LY):

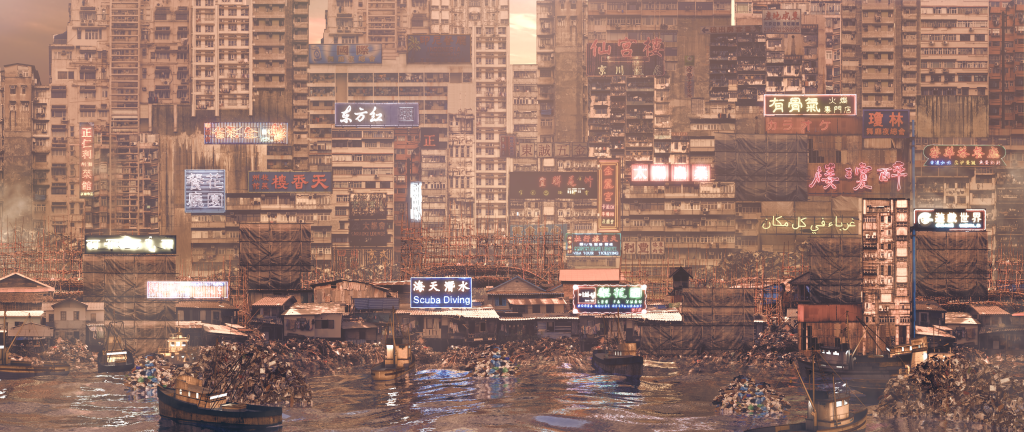

We travel to these extreme locations because we think that – in order to understand the full complexity and the breadth of the modern city – it is no longer sufficient just to look at that particular city in itself as a singular point on a map, but we have designed for ourselves a thoroughly networked condition, in which we exist, where there is not such a thing as a singular site anymore. Every site is implicated in a planetary scale network of relationships, landscapes and territories.

So what we do is really just mapping the site of the contemporary city. In order to that we need to get on a plane and travel to the most remote landscapes in the world to understand the systems that the city sets in motion, because we now live on a planet that has been entirely and totally urbanized. This doesn’t mean that the cities have stretched all over the planet, but certainly the consequences of cities have stretched all over the planet. So the ‘tailings lake’ – a dumping ground for waste products – next to the Baogang Steel and Rare Earth complex, the world’s largest rare earth mineral refinery at Baotou, the industrial city in Inner Mongolia, is a product of all the technologies that we use in our cities. It is the site that produces and is produced by every laptop, phone, wind turbine, electric car that we own and operate.

To get a complete picture of the city and the technology it contains, we have to go to that site in Inner Mongolia. We have to travel to the other side of the planet to Australia because it is where we get the gold that we use in the circuit boards that power every little pieces of technology in our pockets. Travelling to Bolivia and Chile, we see lithium mines used to power all of our technologies.

All these sites are geographically distant, but they are actually fundamental to our everyday experience. So our project is to travel to these places and tell stories about them as a means to make different kinds of decisions back in the cities that we know and we occupy.

Claudia Pasquero (CP):

You have recently been using programmed drones as a tool to map or film your different project sites. What is the possibility to pre-programme drones’ behaviour, and what do they offer in terms of reading contexts, as well as concerning the development of new types of design briefs?

LY:

The aerial view has always been one of extreme privilege, as it used to cost an extraordinary amount of money and been extraordinary complicated to get above the earth and look down on it. We are now in a very interesting moment in which drone technologies have moved out the military industrial complex and into the hands of civilians: there are now more civilian drones in the air than there are military drones. And with any technology, that is a point where it becomes more interesting: when it becomes democratized. Drones are in this amazing point right now as they have just become democratized and we are starting to see the ways in which the public is using them in ways they were not intended for.

So we got interested in drones as a way to access sites that are managed by large international conglomerates, which are protected, with restricted access, because there is this motivation to keep us at a distance from the real site that is being sacrificed at the service of our cities. We launch our drones over these sites because they can fly across fences and territories. They can fly over a factory in India which dyes all of our clothes, but dumps the waste chemicals from that dying process into a sacred river and we can map that process.

We can fly above the Amazon River and map sites of illegal logging in a way that is not possible on the ground. We can fly above the lithium fields that on the ground look like nothing but a white wall of salt, but when you get above them you realize the true extent of these extraordinary landscapes that are required to produce our energy for us.

Drones become a way of remotely operating and accessing sites that we physically cannot go to or access. The impetus for our initial interest in the drones was the possibility to create new forms of agency: drones create new ways of capturing landscapes, understanding landscapes and our relationship to those landscapes. So they became a very central part of our work. But a big part of the methodology of how we operate is that we go to these landscapes, document them and then we extrapolate stories and scenarios to imagine the implications that these landscapes might have on potential futures. We use this process of exaggerating the present into possible future scenarios.

What we have also done with our drone work is to move beyond the idea of just drawing a map from the air, into the idea of thinking about what this new mode of viewing and understanding the world through the aerial lens might do for the new ways of occupying the world and also the new ways this world is constructed.

We have done a whole series of sci-fi speculations that imagine what happens when the drones that we use to fly over these landscapes become almost as ubiquitous as the pigeons in the modern city. Drones that become new forms of infrastructure, that enter into almost every aspect of our life: they deliver objects to us, they become forms of aerial infrastructure, new forms of surveillance infrastructure, new forms of data capture infrastructure. They also become new forms of cultural creatures and strange kind of pets and creatures we tend to keep around us.

I have done a series of speculative projects using drones to try to prototype the different ways these drones are going to change our lives. We have done a speculative short film called ‘In the robot skies’ which is exploring the sub-cultures that emerge in the context of these drone technologies. If we believe that the developments of these drones is going to create autonomous surveillance networks that monitor our cities, then how do you create new forms of resistance and agency around those systems of surveillance?

We developed the story about a guy and a girl that live in a London council estate and learn how to hack these surveillance drones and, like graffiti writers, scribble along the side of a car or a bus, or a train, using those scribbles to write notes to each other and to flirt with each other back and forth across two towers which this surveillance drones network is constrained them to. The film is a love story told through the eyes of a series of drones that have been hacked by these kids, so they can pass love letters to each other back and forth. We programmed the drones with autonomous behaviours because we wanted to really explore what it means for these drones to see the world and what it means for them to understand the world in their own terms. As the director I am not making the sorts of decisions that a traditional film director would make: all I am doing is programming a drone with a particular set of behaviours and the drone makes the choices about the film.

It is really about exploring these new subjects’ positions emerging in cities and technologies where infrastructure, architecture, buildings, objects used to be unheard, and now talk back and have conversations with these elements and make their own decisions: what that does it mean for us as inhabitants of cities when we are now sharing our lives with “walking and talking” pieces of architecture?

The film is really trying to explore those different relationships and that, too, is part of our practice: we have a documentary relationship that explores the world as it is and the speculative relationship that exaggerates that world and explores a series of future scenarios that one might examine and speculate out of it.

MP:

When you run one of your drones, we could argue that you are performing a kind of real time simulation. What is the relationship between the running of a drone in a specific site, and the narrative underpinning your projects and your intervention on the site itself? In other words, how does digital design inform – and in turn how can it be informed – by narrative in your work?

LY:

I rarely work in sites as architectural audiences would traditionally understand them. I don’t design things for particular sites, but rather the sites I am interested in are the sites of popular cultures. For the most part I operate as a film maker, but I am telling stories and making films about architectural questions, problems and propositions.

We might travel to some of these different sites, document them and tell stories about them, but when we are making works for those sites rather the site for that work is back in the places we came from: cities like London or Los Angeles or New York. These are the true sites for our work, where the stories that we create get told and consumed. And similarly the future is a kind of site as we are making propositions for that future. But we are making them again in the medium of films or animation and we are disseminating them on the internet, in film festivals, gallery spaces or in the news media, and these are the kinds of sites where our architecture really operates: it is not operating as schemes in the world, it is operating as schemes within cultural discourses.

This forces an audience into a direct relationship with the architectural and urban ideas that we are developing. And that is our model of affecting change: we are not architects in the sense of making propositions for sites and trying to get them built. We are architects in the sense that we visualize stories, futures and present contexts in such a way an audience can start to connect to them, making up their own minds about them and then enact and create their own changes in the world.

Really it is a strategy of trying to get architecture outside of its disciplinary bubble and have more resonance and scope for change in the world: because traditional forms of architecture are so limited that they require huge amounts of capital in order to happen and we have such a small degree of influence over cities’ spaces even when we are able to build is such a minute proportion of the world that we have access and control over. So what we are trying to do is talk to the people building our cities, making our world and consuming those worlds, and then enacting cultural changes as opposed to disciplinary changes. We are trying to talk to audiences that are not architects, but to the public, and we are trying to engage the public in these questions about how technology is changing their world.

This is a really important challenge for the new generation of architects being increasingly marginalized from the traditional forms of practice that we are trained in, trying to identify new forms of practice that engage with technologies, systems and networks, audiences outside the discipline and in turn with the mediums of popular culture in order to try to stay relevant. Otherwise architects are going be relegated into boutique luxury industries that design Louis Vuitton handbags and rich people’s beach houses.

We need to adapt in order to remain critical and important in the changing faces of cities. Because the forms that once generated cities – the permanent systems of infrastructure, buildings, public squares – have less and less influence on how we exist in the world. So we architects need to better engage with technologies, systems, networks, autonomous infrastructures, mobile technologies, because these are the mediums through which cities are imagined. I think that the tools of the speculative architect, the tools of the story-teller are very important: that’s the way how we conceive our practice.